“GROW soil? You mean you grow plants IN the soil, right?” I couldn’t help exclaiming incredulously to the stocky, bespectacled gentleman in front of me.

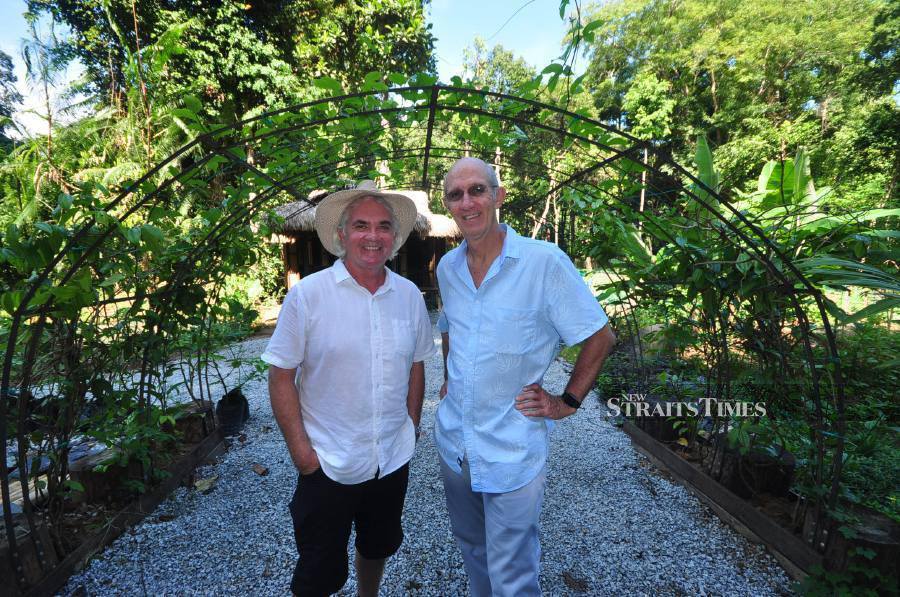

Clad in a light cotton shirt, a straw hat perched jauntily on his head, Mark Garrett, a permaculture design consultant AND the man who designed English business magnate Richard Branson’s Necker Island in the Caribbean, is clearly tickled.

“No, I mean we grow soil,” he replies in his slow and deliberate Aussie drawl, amusement lacing his voice.

Meanwhile, standing by a modest wooden kampong house, which serves as an office of sorts, looking out to a view that I can only describe as an “eclectic” garden, with all kinds of plants and trees and unusual mounds of “natural matters” making up the elements, is a taller, bespectacled gentleman, who’s doing a bad job at containing his grin.

“Let’s go for a walk around this garden and we’ll explain to you how it works,” suggests Piet Van Zyl, the pioneer of Positive Impact Forever (a start-up that’s passionate about making a positive impact on the environment around us) and an experienced sustainability professional with more than 24 years hotel experience.

Garrett, who also redesigned the edible gardens of Green School, the world’s greenest school located in Bali, Indonesia, and Van Zyl are here in Langkawi to lend their expertise to one of The Datai Langkawi’s amazing eco-initiatives, the Permaculture Garden.

In fact, Van Zyl is on The Datai’s Sustainability Committee (Pure Team), where he provides full guidance on all the resort’s sustainability initiatives, and Garrett is the man behind the design of this permaculture garden.

UNDERSTANDING PERMACULTURE

The Permaculture Garden, which is framed on one side by lush natural rainforest, is a zero-waste organic food production system with a closed-loop waste management system. It represents a continuous journey towards developing sustainability within the property.

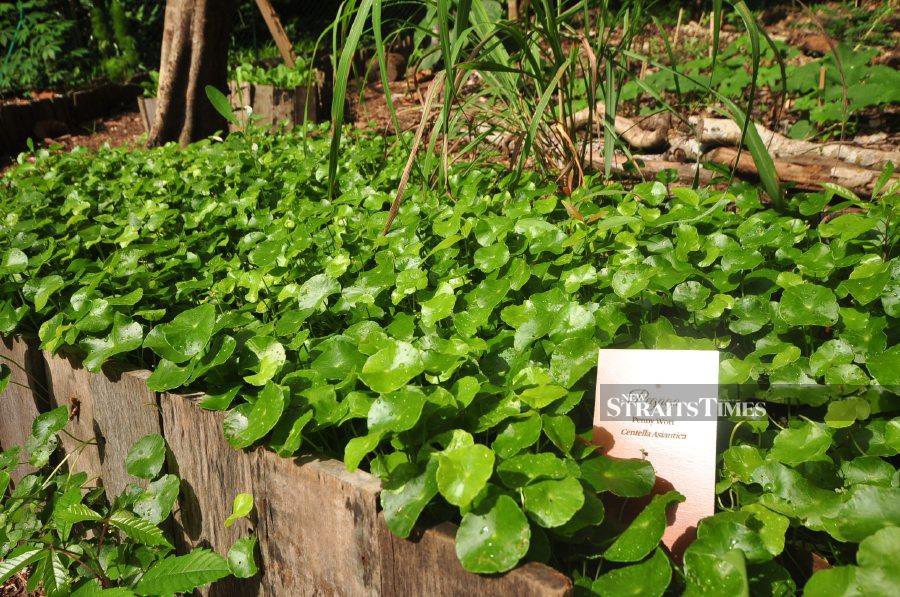

As the two gentleman and I make our way into the “garden”, where banana trees and the pegaga (Asiatic pennywort), peppercorns, pak choi (type of Chinese cabbage) and many, many other plants and trees co-exist in harmony with each other, it’s Garrett who enthusiastically assumes the part of obliging guide.

“As I was saying earlier, we really do grow soil here,” begins the affable Aussie, a specialist in tropical permaculture.

“Apart from climate, the permaculture philosophy also focuses on building up soils so that they can gradually become more nutrient-rich and well-balanced as time goes by. Soil is important because it’s where our food grows from,” he explains.

“Is permaculture the same as organic gardening?”, I blurt out. The question had been floating in my mind ever since I walked into this garden.

“Not quite,” replies Garrett with a smile. Permaculture does use organic farming practices but it goes beyond just that.

In a nutshell, a permaculture garden is different from other modern farming techniques because its focus isn’t just on growing food.

Those who practise permaculture seek to “…find balances between the give and take of nature – including animals – and the needs of humanity.”

Permaculture, elaborates Garrett, is a way of living in harmony with nature by growing food, creating efficient energy systems, saving and reusing water, cultivating diversity, and regenerating soil nutrients and minerals so people can live healthily in thriving environments.

DESIGNING THE GARDEN

As we stroll further into the garden, weaving our way around “plant beds” and pausing every so often to check on the various plants that make their home here, Van Zyl shares that the biggest component of their waste programme is organic waste. “About 80 per cent of the waste is organic. So this is where this began.”

Continuing, he says: “When we decided to embark on this, we realised we needed to have an organic garden where we can bring all the food waste and turn them into compost. The compost can go into the garden; the garden can produce food and the food will go back to the kitchen, thus completing the system.”

And then Garrett, who also provides training and guidance for The Datai’s associates keen to learn about permaculture principles, was brought in to design the garden.

The duo incidentally were already familiar with each other’s work, having collaborated on several projects around the world, beginning with one in the Maldives.

This site which the permaculture garden now occupies was formerly a rubbish dump, where the hotel contractors would dump their discards. But the duo saw potential in the space and decided that it’d make the ideal canvas for what they wanted to do.

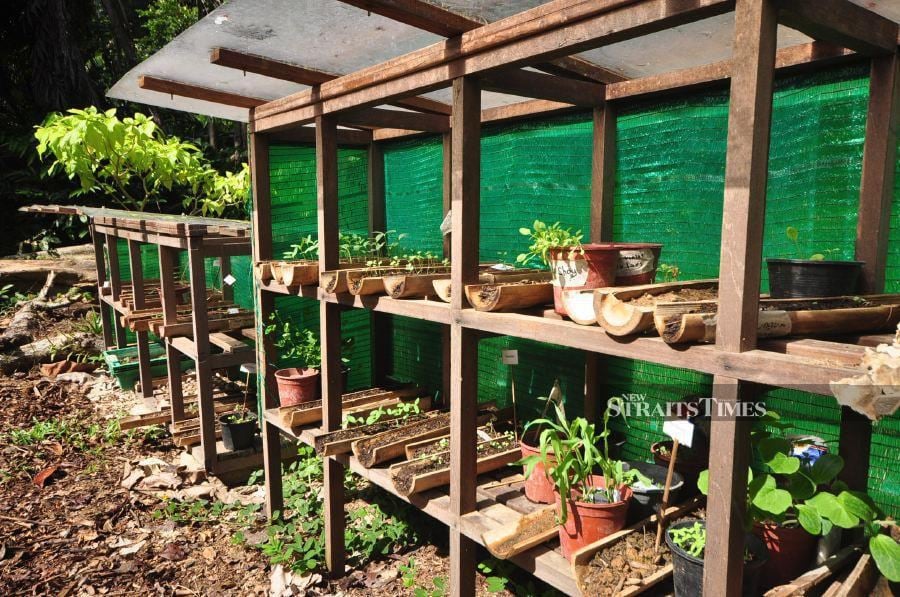

The actual garden area measures around 600 to 700 square feet (about 55-65 square metres). It’s what’s known as an intensive production garden, explains Garrett. Then, there’s the area where the kampong house-cum-office-cum-education space is located, which takes up about 400 square metres.

Another 400 square metres just outside the garden has been allocated for what’s known as the Monkey Forest, where specific fruiting trees and plants are grown in order to lure the monkeys (and wild boars) to remain in one place so as not to disturb the main garden as they search for food.

And finally, towards the back of the garden is where compost is created, other food forests are being developed and a worm farm is being cultivated.

“Wait, there’s a worm farm?” I ask, bewilderment etched on my face.

Garrett throws me an impish smile, saying: “At the back there, we’ve used discarded bath tubs for our worm farm. Instituting a worm farm on a permaculture plot will ensure that you get a consistent supply of castings, which in turn helps your soil to remain in good condition all year round.”

This permaculture garden is a major part of The Datai’s sustainability programme, adds Van Zyl, before sharing that the Pure Centre, located towards the back, is where all the food waste are brought in, dehydrated and then brought back here again for the composting and the worm farm.

Elaborating, Van Zyl shares: “We’ll shred all the plastic and crush the glasses and make other things from them. By middle of next year, the hotel won’t have any waste going to a landfill because everything will be handled onsite.”

HOW IT WORKS

Although permaculture works closely with nature, the duo share that they’re using a lot of science and technology to speed up processes.

Explains Garrett: “We’re using various techniques to grow soil quickly in order to help prepare the land so that it’ll be able to grow food in a healthy, non-pesticide, non-chemical manner. Our composting system enables us to grow a cubic metre of compost within 18 to 20 days.”

Permaculture, adds the biking enthusiast, is the first land-care ethic for any civilisation.

“There’s care for the land, care for the people and creating abundance so that it can be shared fairly with the people of the land. And when we talk about people, we’re talking about every living micro organism on this planet – because that’s just how nature works. It’s all nutrient-cycling and closed-loop systems.”

In nature, chips in Van Zyl, there’s no such concept as waste. The so called waste becomes shelter or food and energy for the next process. “It’s only us humans who create waste that has no further use.“

As soon as guests enter the permaculture garden, they’ll see micro-systems at work and how nature is being used as the guide.

Enthusiastically, Garrett points to what the duo call an herb spa. “This pattern exists in nature too. The benefit of doing this type of pattern is that within three square metres of land, we’re creating over 20 lineal metres of growing space so we can plant up to 20 different herbs and spices in this area. This system increases productivity, increases our yield and also makes it far easier, energy-wise, to give the plants the best opportunity to live.”

Leading me to what appears to be an unusual garden bed, Garrett shares that this is where they’re growing soil.

“This is a no dig raised garden bed (a concept popularised by Sydney gardener Esther Dean in the 1970s, comprising layers of organic material that are stacked up to form a rich, raised garden area).”

Adding, he explains: “There’s no soil here, only sand. We’ve raised it and used old floorboards from the resort. By raising this and filling this up with organic matter and then putting the cardboard on top, we can then put mulch and thus grow healthy soil.”

Healthy soil, interjects Van Zyl, is very important. It produces healthy plants and insects won’t bother the plants much.

“Mark did an experiment in Bali where they had the local people doing their usual garden and he did his. The local garden got eaten up by insects while barely a metre away, Mark’s garden was untouched,” shares Van Zyl, adding: “It all starts with healthy soil. Healthy soil, healthy plant, healthy food, healthy people!”

“Let’s go and see the worm farm now!” exclaims Garrett, beckoning me to follow him to an area in the garden where another kind of magic is taking place.

WORM FARM

The sight of a row of bathtubs filled with rich, dark soil, in the middle of the outdoors takes me by surprise. Peering closely, I notice with alarm worms wriggling happily in the mix.

“So this is our composting worms,” explains Garrett. “We’re adding food waste from the kitchens and buffalo poop to make it work. The worms are an amazing part of the process. They regulate their own population. If there’s a lot of food in here, they’ll go crazy. If there’s no food, they die. It’s a great indication of the soil quality.” And this is where the compost used in the permaculture garden is being created.

Leading me to the other side of the bath tub, where water is traditionally drained out from, I see a concoction, tea-like in appearance.

“This is our worm tea!” exclaims Garrett, chuckling. “We hydrate the worm farm once a week and get this beautiful ‘tea’, which is full of micro-organisms. The water is diluted worm castings.”

Working like a liquid fertiliser, the “tea” is sprayed onto the vegetables every 10 days.

“It helps with pest management and ensures the vitality of the plant,” chips in Van Zyl. “So out of this system, we’re able to get soil and liquid fertiliser, also using so-called waste. I reckon we’d be able to process about 100kg of food waste a day in here!”

MAIN CHALLENGES

Moving away from the worm farm, we stroll in companionable silence around the rest of the garden, enjoying the joyous chirping of birds around us.

Turning to the nature-loving duo as we stop under a shady canopy, I ask them what they consider to be the biggest challenge.

Garrett is the first to reply. “Trying to get people to think like a permaculturist,” he says.

“Once you do, you’ll be able to better understand the connection; that we’re a part of nature and we need to be able to orchestrate these natural-occurring events in nature.”

Emphatically, he adds: “Understand the philosophy and then start looking at the ethical changes you can make. Do you want to care for other people and create abundance? Abundance can be created just by saying ‘no’ to a plastic bag or plastic straws. Once you start thinking like that, a whole world opens up to you.”

Nodding, Van Zyl offers: “Come to The Datai, see what’s being done and be inspired. Start small and then grow big as you get more experience and knowledge.”

DIRT ON THE DUO

The chattier of the two, Garrett, was formerly a registered nurse with a degree in nursing. His interest in the land had much to do with his formative years living in Queensland, Australia.

His mother, he shares, came from a dairy farming background while his father was in agriculture. “Growing up in Queensland, we always had chickens and veggie gardens in the backyard,” recalls Garrett.

But it wasn’t until he saw a documentary with Bill Mollison, an Australian researcher, author, scientist and biologist, and the man referred to as the “father of permaculture”, sometime in 1985 that the 20-something Garrett had an epiphany of sorts.

“It just made sense,” he recalls. “After I saw the documentary, I started pulling out the concrete driveway and planting trees. And then after I moved from that house, I bought some land and designed a house from scratch using permaculture principles.”

In 2009, Garrett returned to Australia after a stint of travelling and living around the world doing various things.

“I enrolled myself on a course and realised how little I knew. So I decided to spend more time with Bill (Mollison) who told me, ‘Pick a couple of books and go and see what you can do!’ So now I’ve been to over 15 countries and still carry the same few books with me. It has become my full time profession for the last 10 years now.”

Meanwhile, Van Zyl was brought up in the city but at the age of 10, told his parents that he needed to live on a farm.

Smiling, Van Zyl recalls: “I just couldn’t stay in the city anymore. When I turned 11, my parents sent me to a boarding school on an agricultural farm. There I learnt much about farming.”

That said, a farmer’s life wasn’t for him, confides the soft-spoken South African.

“I didn’t have a father who had a farm. He was in the military. I decided to become a civil engineer instead.”

He ended up in Fiji sometime in 1993 where he met a guy who had a resort there located on a coconut plantation.

“I was asked whether I wanted to come and manage his resort. It was funny because I didn’t actually have any experience but I went for it anyway. We managed to build it up nicely.”

And that’s how his foray into the hotel industry started. Beginning as a general manager, Van Zyl then went to different places, including the Maldives, before ending up in Bali and assuming the role of group director of engineering and sustainability for Alila Hotels.

He left Alila last year knowing in his heart that sustainability was his true calling.

“It’s just a passion that needs to be shared. And here I am,” concludes Van Zyl, his kindly eyes behind his glasses lighting up with happiness.

For details, go to www.thedatai.com