“MALAYSIAN Red Crescent Society (MRCS) has a new chairman!” my friend, a retired school teacher, exclaims over the phone one morning. Still very much involved in the society’s affairs at the Kota Star district level, he added that everyone he spoke to was pleased with Tan Sri Tunku Puteri Intan Safinaz Sultan Abdul Halim’s recent appointment.

“It’s a historic moment for all our members as the Kedah princess, who is also the state’s Tunku Temenggong, is the first female to head MRCS since its establishment seven decades ago,” he adds before urging me to join him on a planned recruitment drive to encourage further youth participation.

His words strike a chord with me and trigger my interest to dig up interesting facts about the society’s origins that may prove useful during the membership campaign. Over the next few days, my research brings me on a most exhilarating learning endeavour that starts with Swiss businessman Jean-Henri Dunant who, in the mid-19th century, lived in a time when there were no organised or established army health care systems.

How it all began

In June 1859, Dunant travelled to Italy to meet French emperor Napoleon III with the intention of discussing difficulties in conducting business in French-occupied Algeria. He arrived in the small town of Solferino on the evening of June 24 and witnessed the aftermath of a deadly battle where 40,000 soldiers died or were left wounded on the field.

Dunant was so taken aback by the near-total lack of medical attendance and basic care for the wounded soldiers that he completely abandoned his original intent and set out to help with the treatment and care for the victims. He rallied the local villagers and convinced them to participate in providing relief assistance.

Upon his return home to Geneva, Dunant wrote and published a book entitled A Memory of Solferino in 1862. To raise awareness to his cause, Dunant sent copies to leading political and military figures throughout Europe and began advocating the formation of national voluntary relief organisations to nurse wounded soldiers. At the same time, he also called for the development of an international treaty to guarantee absolute protection for medical personnel on the battlefield.

In 1863, Gustave Moynier, president of the Geneva Society for Public Welfare, read Dunant’s book and subsequently organised an international conference that successfully deliberated the possible implementation of Dunant’s ideas.

This meeting encouraged the Swiss government to invite the governments of all European countries, as well as those from the United States, Brazil and Mexico, to attend an official diplomatic conference held on Aug 22, 1864.

The summit ended with the signing of the first Geneva Convention and the adoption of a common distinctive protection symbol, in the form of a white armlet bearing a red cross, for all field medical personnel.

A few months later, Louis Appia and Charles van de Velde, a captain of the Dutch Army, became the first independent and neutral delegates to work under the symbol of the Red Cross in an armed conflict.

Chaotic War Years

In 1876, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) came into existence. Five years later, Clara Barton helped start the American Red Cross. As more and more countries signed the Geneva Convention, the Red Cross rapidly gained momentum as an internationally respected movement and a popular venue for volunteer work.

As a tribute to his key role in the formation of the Red Cross, Dunant was awarded the first Nobel Peace Prize in 1901. Sadly, he died nine years later in the small Swiss health resort of Heiden. In remembrance of his contributions, Dunant’s birth date, May 8 was later designated as World Red Cross Day.

By the time First World War broke, there were already 45 national relief societies throughout the world. The movement had extended beyond Europe and North America to reach Central and South America, Asia and Africa.

During those chaotic war years, Red Cross nurses from around the world came to support the European medical services involved in the war. On Aug 15, 1914 the ICRC set up its International Prisoners-of-War (POW) Agency, staffed by 1,200 volunteers. Throughout the duration of the four year war, the Agency distributed 20 million letters and messages, two million parcels and about 18 million Swiss francs in monetary donations to POWs of all affected countries.

The Agency also facilitated the exchange of about 200,000 prisoners between warring factions. The accumulation of about 7 million records through inspection visits to POW camps from 1914 to 1923 also helped to facilitate the identification of about 2 million detainees and initiated the ability for them to establish contact their families.

A year before the end of World War I, the ICRC received the 1917 Nobel Peace Prize for its outstanding wartime work. It was the only Nobel Peace Prize awarded throughout the duration of the war!

Awareness grows

Capitalising on this prestigious recognition, the Red Cross embarked on a series of fund raising exercises to finance its various humanitarian activities designed to alleviate the horrors of war. In Malaya, this was achieved by overprinting selected postage stamps of the Straits Settlements and Terengganu with special Red Cross surcharges.

Looking at my Terengganu postal history collection with fresh eyes, it becomes obvious why the stamp issue created such a buzz among local philatelists. Stamp collectors were delighted beyond words when they discovered a plethora of varieties and errors on the overprints which consisted of the words RED CROSS printed across the top of the 3 cent carmine, 4 cent orange and 8 cent blue stamps.

The hastily prepared overprints also had the additional surcharge of ‘2c.’ printed at the foot of the stamps bearing the portrait of Terengganu’s then ruling monarch, Sultan Zainal Abidin III Muadzam Shah.

The situation at the Terengganu post offices turned chaotic as philatelists clamoured for notable printing errors like RED CSOSS and the figure 2 in thick block type. The glaring mistakes clearly showed that the process was done in a haphazard and rushed manner.

Fortunately though for the Red Cross, these varieties helped to drive sales and awareness towards the society. On Dec 20, 1917, the Straits Times reported that total sales in Kuala Terengganu alone amounted to nearly $369.

The Japanese Occupation

As the Malayan branch of the British Red Cross was only founded some 32 years later on Sept 30, 1949, these Terengganu stamps, together with their counterparts issued in Penang, Melaka and Singapore post offices, represented the first widely publicised event promoting this international humanitarian society.

The arrival of the Second World War in Malaya saw the internment of thousands of Allied nationals in POW camps in the country. Again, Red Cross volunteers came out in force to play a crucial role in collecting information about the prisoners as well as initiate relief supplies and mail delivery from the anxious family members.

The Japanese Army officers, on their part, behaved in an indifferent manner when it came to the care of their 300,000 prisoners. In April 1942, the Australian Red Cross representative in Malaya’s largest POW camp in Changi secured a meeting with General Tomoyuki Yamashita and obtained promises for a complete list of the prisoners and the construction of a comprehensive canteen equipped with medical supplies. Plans were also put in place for the Red Cross representative to be given a car and a free movement pass.

The POWs were overjoyed when told of the news and thought that better days were ahead as far as their living conditions were concerned. Sadly though, their elation was short lived. Just a few days later, on April 14, 1942 those privileges and promises were abruptly and permanently withdrawn.

More of such heart-breaking setbacks took place during the Japanese Occupation and, as a result, the ICRC representatives in Malaya had to wait until the closing stages of the war to finally be able to work openly and effectively as distributors of Red Cross relief supplies.

Another stumbling block to the Red Cross efforts during the Second World War was the slow and haphazard distribution of POW letters and parcels. When questioned by the ICRC, the Japanese officials often placed the blame on censorship procedures, where each and every letter had to be scrutinised prior to their onward transmission.

The censorship department was naturally inundated with work and its officers often took the easy way out by putting large amounts of untreated mail into storage. Piles upon piles of uncensored mail were found in Japanese POW camp offices throughout the country when British forces returned to liberate Malaya in early September 1945.

Red Cross in Malaya

The Red Cross answered the call for help yet again when Malaya faced the communist terrorist threat in 1948. In an effort to win over the heart and minds of the people, and at the same time deprive the bandits of local support, Field Marshal Gerald Templer intensified psychological operations in the new villages by bringing in large numbers of British Red Cross and St John Ambulance personnel.

Apart from providing an insight into the workings of the government and successfully helping to counter deceitful communist propaganda, these volunteers also gave much needed medical services to the local population.

Throughout the Emergency, the Red Cross operated mostly out of government hospitals. In Pahang, the British Military Hospital (BMH) at Tanah Rata became one of their main bases. Moving Red Cross personnel and casualties in and out of the place, however, proved to be a constant challenge as the hospital was surrounded by dense jungle infested with communist terrorists.

The Red Cross staff at the BMH catered primarily to recuperating personnel who came from all branches of the armed services in Malaya, including Singapore. The wounded men arrived by armoured train at the Tapah Road Railway Station. After that, they were taken by ambulance up to the BMH with heavily-armed police escorts.

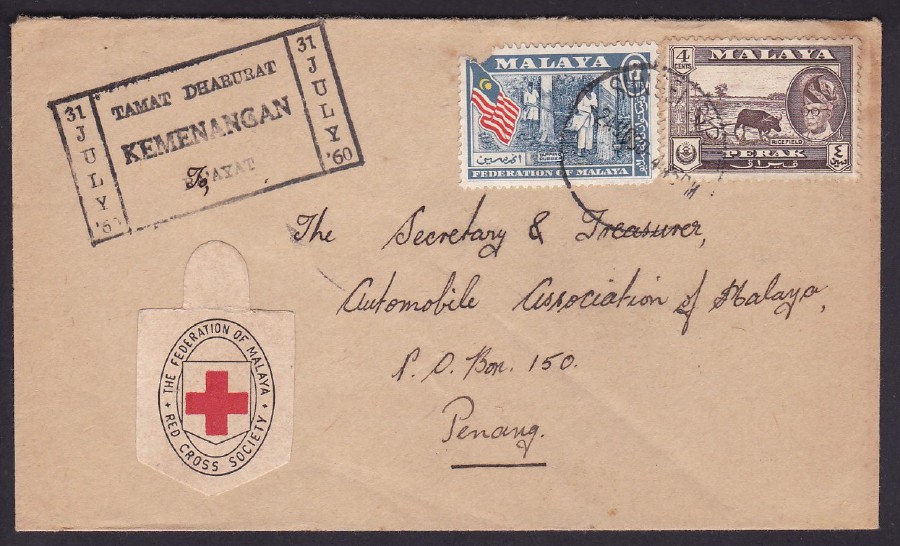

In 1950, the British Red Cross Society staff serving in the Malaya established the society’s first branch in Penang. Within two short years, branches were set up in six other states — Terengganu, Perak, Selangor, Melaka, Johor and Pahang. After Independence on Aug 31, 1957 these branches were reorganised as the Federation of Malaya Red Cross Society (FMRCS).

The Society’s Calling

A small Red Cross medal and photograph collection that I acquired some time ago reminds me of the time when many young Malayans were attracted to the FMRCS with the desire to further their knowledge of basic health care and medical aid practices. Over time, examination boards were established and those who excelled were awarded medals and given rank promotions.

On July 4, 1963 the FMRCS received official recognition as an independent national society by the ICRC and was subsequently admitted as a member of the League of Red Cross Societies a little more than a month later, on Aug 24, 1963.

With the formation of Malaysia on Sept 16, 1963 the FMRCS was renamed the Malaysian Red Cross Society (MRCS) after combining with the existing Red Cross societies in Sabah and Sarawak. About 12 years later, on Sept 5, 1975, the Malaysian Parliament passed the Malaysian Red Cross Society (Change of Name) Act to effectively change the society’s calling to that of the Malaysian Red Crescent Society.

As I return my treasured items to their respective storage boxes, it suddenly dawns upon me that our Malaysian Red Crescent Society certainly does have a long and proud history. By making this fact known, I hope that more youths will step forward to volunteer their time and effort in support of the society’s various disaster relief and recovery programmes.