MAKKAH was a trading centre long before the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) lived there. Before Islam was fully established, it had also been a place of pilgrimage, although of such a pagan nature that the Prophet was outraged by the tawdry assortment of deities on display. When the pilgrimages resumed, the connection was with the one true God that Islam proclaims, and this has proved to be very popular ever since.

Now that the Haj is over, 2.5 million pilgrims have been journeying back to their homelands. For centuries, this has meant returning with plenty of souvenirs. It’s an ancient tradition, which has included everything from prayer beads to tooth-cleaning twigs.

The key to the Kaabah fetched around RM50 million 10 years ago when it was sold at auction. There was huge disappointment all round when the gorgeous key was found not to be authentic. A record price of more than RM15 million, which wasn’t cancelled later, was paid for a gold dinar from the 8th century. It was made for an Umayyad caliph, but what gave the coin its exceptional value was that it was made from gold that came from his own personal mine. Located near Makkah, the mine is still producing gold today although not at anything like the RM3.5 million per gramme this dinar fetched.

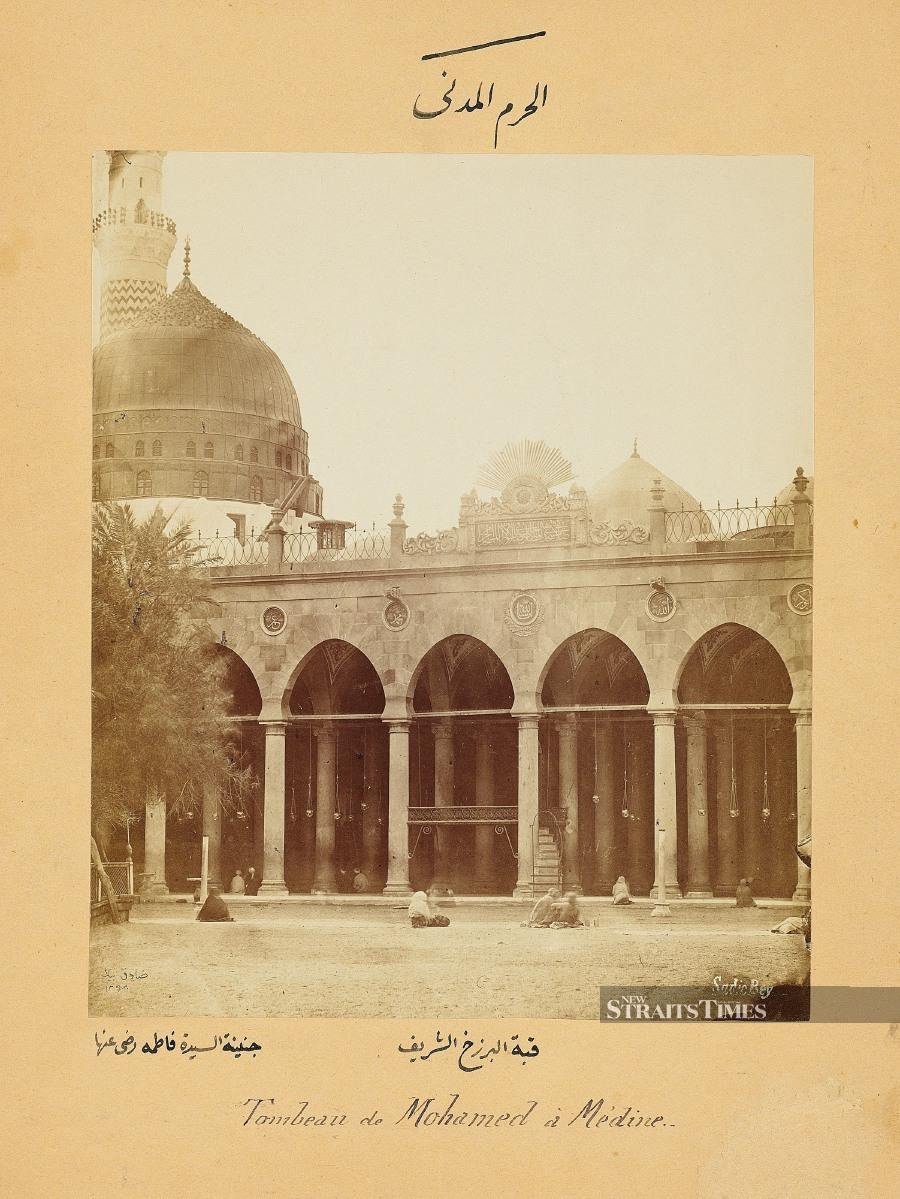

Excluding the digital variety, photographs are no exception to the value of objects with a Makkah connection. Sotheby’s continues to hold the auction record for the first photographs of the Holy City, which were sold in a London sale more than two decades ago for RM6.5 million. The unbeatably high price was partly because of the subject matter but also because the photographer was from the Arab world himself. It was also a time when Gulf money flowed through the art market in a way that has yet to be repeated.

Prints by the Egyptian photographer Muhammad Sadik Bey, who took these photos around 1880, are extremely rare. Muslim artists in Western media are in a small minority, with massive demand from collectors eager to participate in a past that was rarely recorded by non-Westerners. Among 19th-century painters, the Ottoman Turkish Osman Hamdi Bey, is the pre-eminent exponent. If he had taken his easel to Makkah and the Haj, demand would go to an even higher level for an artist whose work already fetches more than RM10 million at auction.

Joining this competitive situation is a native of Makkah, who was the first Arab photographer of the city. Curiously, his work isn’t nearly as expensive as Muhammad Sadik Bey’s. This could perhaps be because he wasn’t as elevated in local society, or perhaps it’s the perception that he was the sidekick of an enterprising foreigner. Curiously and confusingly, the local Makkah doctor, Abd al-Ghaffar worked with the Dutch scholar Christian Snouk Hurgronje, who adopted the same name as his amateur-photographer colleague.

INTREPID DUTCHMAN

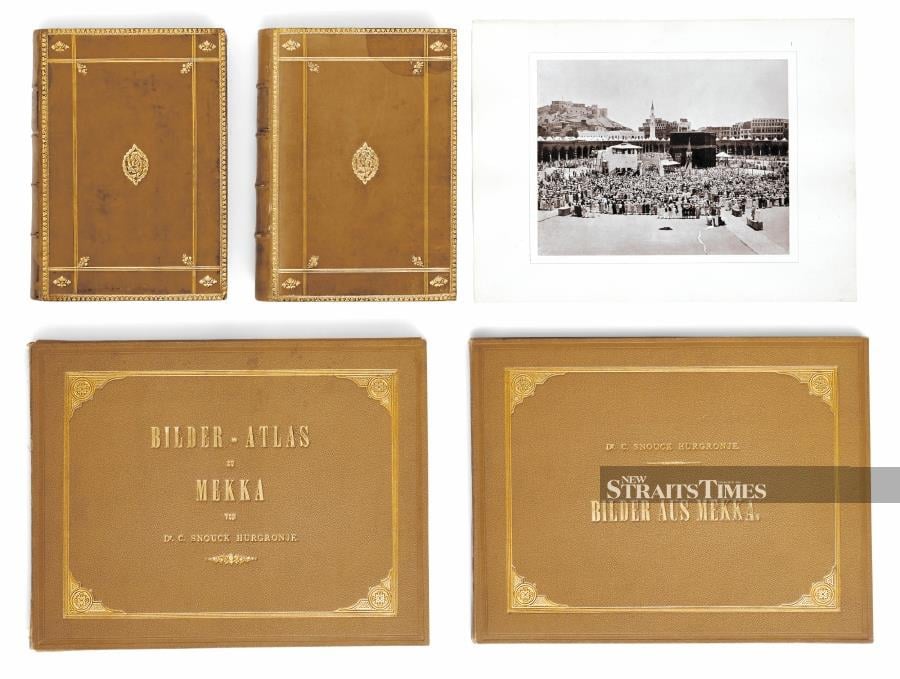

Earlier this year, a personal photo album by Snouck Hurgronje sold at Sotheby‘s for more than a million ringgit. Snouck Hurgronje’s Mekka and Bilder aus Mekka consist of two volumes from the mid-1880s when he worked at the Dutch consulate in Jeddah. In addition to purportedly converting to Islam, he was also likely to have been used as a spy by the Dutch authorities for surveillance of the Indonesian elite who frequented the Arabian Peninsula.

After learning Arabic in the multicultural environment of Jeddah, Snouk Hurgronje went on to get permission to enter Makkah. This was an exceptional distinction for an individual who’d started life as a non-Muslim and whose conversion was questioned at the time and has been ever since.

Having adopted the Muslim name Abd al-Ghaffar and apparently going through the circumcision process, he went on to perform the same rites in Makkah as any Muslim-born pilgrim.

Being a legitimate visitor to the Kaabah, unlike imposter-explorers such as Sir Richard Burton, enabled him to make such confident statements as: "I made acquaintance with modern Makkah society at first hand, heard with my own ears what that international population learns and teaches… I have studied the ideal and the reality… in mosque, divan, coffeehouse and living room.”

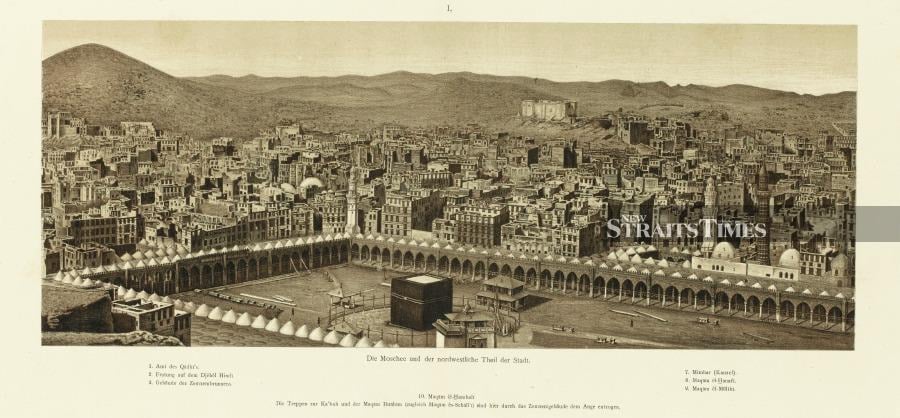

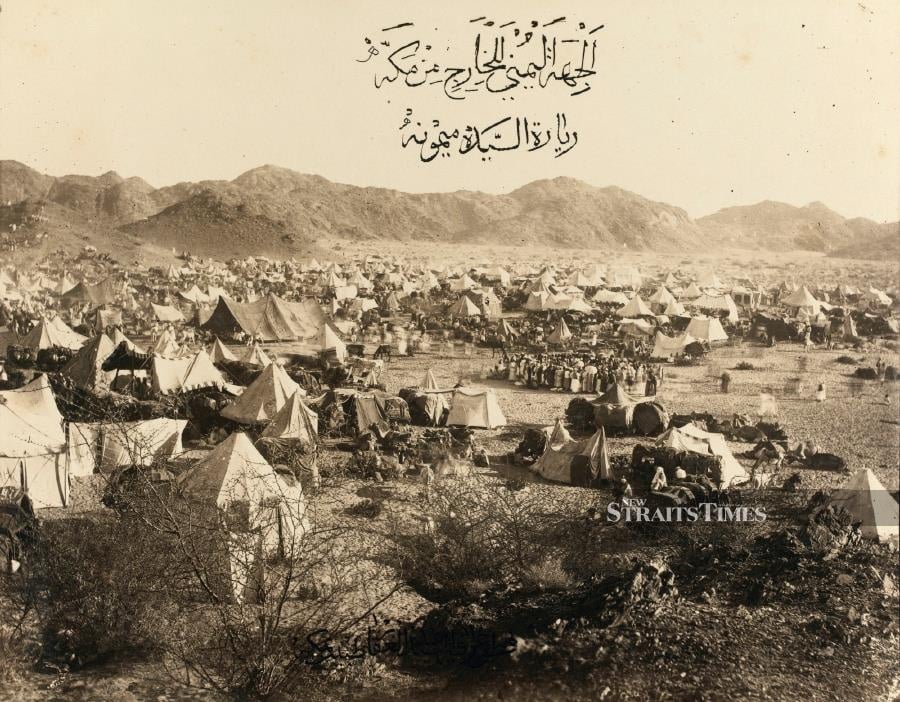

On his return to the Netherlands, he published the largest single illustrated monograph on Makkah of its time. The first volume contains a written survey of the city’s history, while the second examines the daily life of the inhabitants. The plates are among the earliest published photographs illustrating Makkah and its pilgrims from all parts of the Islamic world. The photographs were a joint effort by Snouck Hurgronje and the other Abd al-Ghaffar (Dr), who’d been taught this exciting new skill by the Dutch scholar.

AN UNFORTUNATE END

After the enthusiastic reception to this publication, Snouck Hurgronje published a further set of photographs in 1889, titled Bilder aus Mekka. Makkah was, and still is, a place that’s little understood by the many who will never be able to visit. His description removed much of the mystery and added a new level of respect. Surprisingly, from a 21st century viewpoint, he was adamant about the level of freedom experienced by the women of Makkah.

In the five months he resided there, he was able to look objectively at a society that was as impenetrable as any on earth. In this he was helped by his friendship with his namesake, Abd al-Ghaffar. Photography was pretty much a team activity at a time when cameras were extremely heavy and the chemicals, toxic. Snouck Hurgronje’s debt to his colleague is increasingly recognised, and the photos at the Sotheby’s sale are credited to both pioneers of this unique East-West collaboration.

Unfortunately, the Dutch scholar’s inspirational time in the Holy City was brought to an unexpected end by accusations that he was about to steal some local heritage. He wouldn’t have been the first visitor to the Islamic world to do this, but this was Makkah. His probable innocence made no difference.

He was expelled from the city he so admired and had to abandon his pregnant Ethiopian wife and his photographic equipment. The intrepid Dutchman never returned, and no other non-Muslim visitor has provided such a comprehensive view of this sacred location. The aspect that has really changed is the appearance of the city. Whilst the Kaabah looks substantially the same, the view beyond is unrecognisable. The once-rugged landscape is now blocked by some of the most luxurious hotels and condominiums on the planet, along with the largest clock face.