The 2016 Olympics in Rio de Janeiro this week will not only be the first to be held in Latin America or the first to field a group of refugee athletes competing under the Olympic banner, Olympic Refugee Team (ORT), but will also see an increasing number of Muslim sportswomen participating in a motley of events.

While Muslim men and women have regularly participated in sports all over the world under the “usual” conditions, it is the emergence of female athletes from ultra-conservative Muslim nations in the Middle East that has steered attention to them, especially in what they wear and with whom they mix at sports events.

Muslim men, to whom the sociocultural rules of modesty equally apply, and which are often overlooked and ignored by the self-styled gatekeepers of such mores, have progressed and proliferated in sports unencumbered by such distractions as dress code.

Muslims and sports, contrary to popular misconception, have generally had a mutually beneficial coexistence over the years, without compromising principles. Take, for example, Muslim contribution to the development of rugby in South Africa despite the huge adversity of colonialism and racism over the centuries.

Historical evidence suggests that the Muslim Cape Malays, descendant from the Malayan archipelago, especially Batavia, took to rugby like fish to water. Rugby matches in those days were like social events.

The Cape Malay culture is vibrant and outgoing, and women have always participated fully in community life, including rugby occasions such as the traditional Rag — the local derby between Young Stars from the Bokaap (Upper Cape) and Caledonian Roses from District Six — a history going back to 1936, and a rivalry at the time similar in local intensity to that between Liverpool and Everton or Arsenal and Spurs in the English Premier League.

In fact, it was the Cape Malays who founded the Western Province Coloured Rugby Union (WPCRU) way back in 1886, just three years after the Whites-only Western Province Rugby Union was established.

The clubs that founded the WPCRU included such names as Arabian College, Roslyns, Hamadiahs, Violets and Good Hopes, which in those days were largely formed from district enclaves or even streets in the mainly Malay District Six and Bokaap areas of inner Cape Town. Photographic evidence points to the fact that Arabian College was established in 1883 and Roslyns as early as 1881. The Arabian College team photo of 1883 conjured up the vision of the team in its rugby togs, but with each member wearing the Muslim fez, an essential accessory of the male Cape Malay.

The historical evidence also points to a similar deep-rooted involvement of Muslim Indians and Cape Malays in the development of cricket in South Africa with clubs such as the Ottomans showing the way.

There are such historical gems involving Muslim contribution to sport in several other countries. Incidentally, according to Rugby Afrique, the international body responsible for the promotion of rugby in Africa, rugby is the fastest growing sport in non-traditional Africa among schoolgirls and women, with Tunisia and Morocco leading the way.

In more recent times, however, the relationship between religion and sports has also changed, evolving perhaps with changes in society, politics, economic wealth and, crucially, governance, and affecting not only Islam, but also other faiths, including Christianity, Judaism, Hinduism and Buddhism.

In the case of Muslim countries, the post-1973 oil wealth explosion, and the impact and seeming influence of two ultra-conservative strands of Islam — Wahabism in Saudi Arabia and the so-called Islamic Revolution in Iran — and their reach through money politics in countries such as Afghanistan, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Iraq and Lebanon, have introduced a new stridency and confidence in pushing what some have called a quasi-Salafist agenda in society, including sports.

Iran, for instance, banned women from attending men’s football matches. Saudi Arabia recently had the audacity (and some say the nerve) to suggest to the International Olympic Committee (IOC) that it would like to jointly bid to host the Olympics with neighbouring vassal, Bahrain, on condition that the men’s events would be held in the kingdom and the women’s events in Bahrain. In this way, it would institutionalise gender apartheid in the modern Olympic movement for the first time. IOC, to its credit, showed short thrift to such ideas.

Such a mindset is not the monopoly of Muslims. Some Scottish Presbyterians still scoff at the idea of holding sports events, such as football matches, rugby international and the Open Golf tournament, on the Sabbath. Michael Jones, the New Zealand All Blacks rugby captain, refused to don the famous black jersey on a Sunday for the same objection. Many footballers openly apply the Holy Trinity crucifix sign as they enter the field of play.

The trade mark of Mo (Mohammed) Farah, the double and defending Olympic champion for the 5,000m and 10,000m, after winning a race is to do the sujood, the ritual prostration of the prayers, on the ground. There is nothing wrong with such expressions of religiosity in sports. In fact, it can be performance and character enhancing. It does, however, become an issue when it is arbitrarily imposed based on selective interpretations of creed, culture and tribal conservatism.

To its credit, the IOC and Fifa, the world governing body for football, have tried to negotiate sports issues relating to cultural sensitivities with a fairly open mind. In early 2014, for instance, Fifa approved the use of hijab in women’s football.

Female participation in public sports, let alone international events, from ultra-conservative Muslim nations have, until a few years ago, been virtually unheard of. This was primarily due to cultural objections relating to socio-gender dynamics, very often erroneously couched in the cloak of religious proscriptions.

Female Muslim athletes from countries such as Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria, Central Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa and even Iran and Pakistan have, nevertheless, flourished over the years. Some of them have excelled and gone on to become world and Olympic champions.

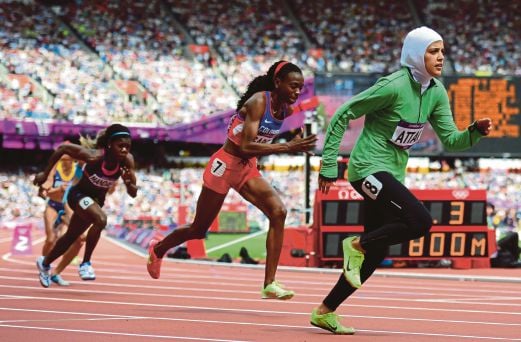

Since the 2012 London Olympics, the world has witnessed the participation of a record number of female Muslim athletes, and there is every sign that this number is set to increase at Rio 2016, but with a difference. While in London it was the odd Saudi or Emirati or Iranian athlete donning a hijab led by the likes of Saudi-American sprinter Sarah Attar and Omani colleague, Shinoona Salah Al-Habsi, in Rio more Muslim women athletes are expected to compete in outfits complete with hijab, not only from traditionally conservative nations from the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries and Iran, but also from others, such as the United States.

In Rio, for instance, Ibtihaj Muhammad will make history when she steps into Carioca Arena 3 for her first match in the women’s sabre fencing competition, becoming the first US athlete to compete in the Olympics wearing a hijab. Other athletes due to compete in Rio donning the hijab include Iranian-Balarus shot-putter Leila Rajabi and UAE weightlifter Aisha Al Balushi.

The hijab issue is very sensitive in secular countries such as France, the Benelux countries and Austria. When French international footballer Jessica Houara-d’Hommeaux of Algerian descent posed for a photo in the French magazine, Surface, wearing a hoodie like a hijab headscarf and soccer netting over her face similar to a niqab, which is banned in France, there was an outcry, suggesting that she was making a political gesture.

Sports, however, can be a great equaliser albeit very often steeped in irony and contradictions. Enter the brave new world of the “sports hijab”. Countries in which the hijab is frowned upon and the niqab banned — at least some of their companies and fashion designers — are capitalising on a new business opportunity — the manufacturing of state-of-the-art garments for hijabis using the latest breathe-easy and temperature-control fabrics. These are emerging in a motley of sports — athletics, figure skating, triathlon, swimming and fencing.

Capsters in Holland, one of the most Islamophobic countries in Europe, is one such company carving out a reputation in designing and manufacturing sports hijab gear, and making a neat little profit in the process.

Most Muslim sportswomen, however, do not dress differently from their fellow non-Muslim competitors, ranging from Tunisian Olympic 3,000m steeplechase gold medalist Habiba Ghribi to Azeri Taekwondo champion Farida Azizova to hundreds of others from all over the world.

They do not have personal and cultural issues relating to a sports dress code. It is their personal choice as self-respecting adults. It would be a great injustice and self-defeating if ultra-conservative Muslim member countries tried to get IOC, Fifa and other world sporting bodies to impose a blanket dress code on Muslim sportswomen. That in itself would defeat the very Olympic ideal of achievement through hard work, and the spirit of tolerance and understanding.

Mushtak Parker is an independent London-based economist and writer