Batik gets a different look with Batik Tektura, writes Aznim Ruhana Md Yusup.

TRADITIONAL batik patterns are typically inspired by nature. The ones produced on the east coast of Peninsular Malaysia for example, are known for their lush floral designs.

Produced using either the hand-drawn or block technique, the patterns are said to carry meaning. But modern consumers are mostly looking for aesthetic appeal and conventially, colours tend to run on the riotous side - it's not unusual to see up to a dozen different shades on a single piece of fabric.

While those are the unspoken rule of Malaysian batik, a local label called Batik Tektura is doing things differently. Founded around 2016 by lifelong friends Azrina Lasa and Yez Yusof, they find inspiration in buildings and architecture.

This is seen in the confluence of angled lines over a palette that is often dark with contrasting shades to make the designs pop. Made in Terengganu and utilising the block technique, the result is batik that is contemporary and unconventional.

As the creative partner of the brand, Yez draws on her lifelong experience with batik to create the designs. Hailing from Terengganu, she played around with melted wax and dye since childhood. It continued when she was in boarding school with Azrina, where they both learnt to make batik in an elective class.

While Azrina admits that she didn't take very much from the experience – her appreciation of batik came later – Yez continued her lessons beyond what was required of the students. As a working adult, she made batik paintings and messed around with tie-dye.

Then a few years ago, Azrina told Yez about wanting a different kind of batik than what was available in the market. As it turned out, Yez was thinking the same.

LIGHT AND SHADOW

"We decided early on to go for an architectural design reference," says Yez, who is a practising architect. "We needed something to hold on to, you see. So with that, I have definite ideas and concepts to play around with. "

"It's also modern and something that I like," Azrina interjects. "The first couple of designs were still a bit floral-inspired but by the third release called Lorek for Hari Raya last year, we can really see that architectural influence."

Lorek or flecks of shade features angled and shaded geometric lines in seemingly random arrangements. It plays with the layering of wax and dyes to create coloured segments that is in contrast with its background. To me, it's reminiscent of cladding on some fashionable buildings.

"We started the venture as a labour of love, something for ourselves and for friends and family," says Azrina. "But because I document the journey on Instagram, we attracted attention from the public and we began to get noticed at weekend bazaars."

But getting to that point was not easy. Folks in the industry said what they wanted to do was too complicated and the design had to be hand-drawn. The duo even considered digital printing, before aborting the idea.

"Finally, our batik blockmaker Pok Ya introduced us to a batik workshop, which agreed to produce the fabric for us" says Yez. "But the way we work, it's more of a collaboration. The workshop gives input on colours and block placement. I also discuss new block designs with them and Pok Ya.

"So it's a whole ecosystem of people working together, not just me giving instructions."

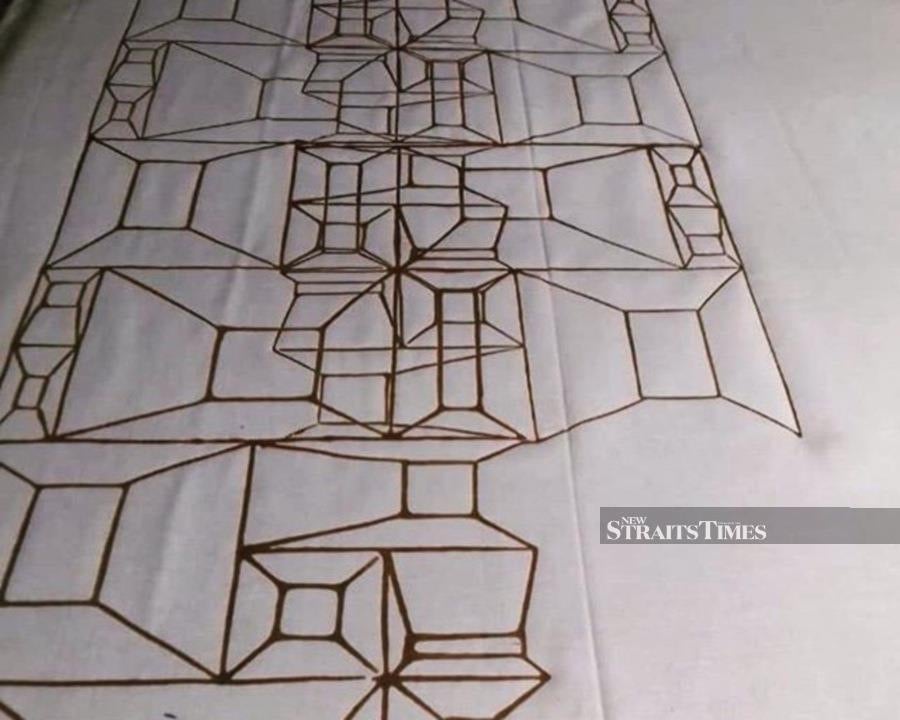

The latest design from the duo is called Bayang or shadow, which they released in time for this year's Hari Raya celebrations.

The basic pattern features overlapping blocks of squares and rectangles, while variations are created by additional stamping of the blocks.

One variation follows the style of batik sarung or kain pelikat, where there is a small, disparate section called the "head". This makes it tricky for sewing into tops, but works well when made into a sarong, especially when paired with the shorter kurung kedah top.

The inspiration for Bayang came from Yez looking at mid-century modern architectural works, the likes of Le Corbusier and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.

"Just like in my work as an architect, I would look at precedents." says Yez. "So the pattern is actually that of recessed windows. When a window is recessed and you have light coming in, you get shadows. The blocks are what the shadows would look like.

"That's where architecture comes in; we get inspired by an architect's work and see how it can be transformed into something wearable."

FUTURE OF BATIK

Meanwhile, the previous collection is called Silang or criss-cross. It looks like a random, chaotic mess of lines but there is order, Yez assures me. There is also order to how the blocks are stamped onto the fabric, to ensure that the lines meet seamlessly across the entire length of the fabric.

The Deret (or row) collection is their take on minimalism with patterns of converging lines and solids. They produced a special collection in red for Chinese New Year featuring soft furnishing items such as table runners and placemats.

The duo recently advanced to the second round of Piala Seri Endon, an annual competition for Malaysian batik designers.

It's a first for them, and they entered the soft furnishings category as a challenge for everyone involved.

"We also brought in the blockers from the workshop to give them exposure," says Yez. "It's how we help them to come out of their shell so to speak, and to see the potential of batik beyond the clothing fabric they usually do."

"Because our design is quite minimalist compared to others, we're not sure how well we're going to do in the competition. But the judges did see the strength in what we're doing, and the category considers commercial viability as well. So I'm using all my experience in interior design to make sure it's up to mark."

Another reason that makes the brand distinct is its choice of colours. Interestingly, the dark, limited palette is both a choice and an imposition.

They explain that the batik workshop soaks the stamped cloth in dye to colour it, as opposed to brushing in the colour. This way, lighter colours need to be applied first. When the fabric is dry, another layer of wax is stamped onto the cloth followed by a soak in dye of a darker shade.

The cloth needs to be dried on a laundry line, and the line can have the unforgiving nature of leaving a mark on the drying fabric. This requires an attentive worker to move the fabric every few minutes, so it's just simpler for everyone if a darker colour is used.

It's clear that batik is not a simple process, and there are several other things holding the industry back. This includes being reliant on imported materials such as dyes and fabric, as well as a shortage of artisans and batik workers.

According to Yez, this isn't due to the lack of training programmes by government agencies. But rather, the laborious working requirements such as working with hot wax and relative low wages that make young people seek employment elsewhere.

There are issues among consumers as well, such as the misconception of batik.

"Many people still think of batik as a pattern, instead of a technique," she says. "We'd encountered sceptics who say our products don't look like batik even though it's the real deal. But when you understand the process, you can create something new.

"But we have no intention to interrupt the industry or change the look of Malaysian batik. We can't dictate people's tastes, we only want to give people a choice and in our own way, uplift and contribute to the industry," adds Yez.

Into batik these days? Shop the latest batik collection and use Zalora discount code to save your money.